The AI assistant will see you now

Today: How Houston Methodist is using a generative AI assistant to check in on discharged patients, why AI coding assistants might soon be billion-dollar properties, and the latest enterprise moves.

The rise of the cloud was not just a transition from owning computers to renting them; it also ushered in enterprise computing resources that were scalable and flexible. Oxide Computer is a bet that enterprise tech wants to run the cloud model in its own data centers.

The rise of cloud computing was not just a transition from owning computers to renting them; it also ushered in an entirely new way of consuming enterprise computing resources that was scalable and flexible. Oxide Computer is a bet that enterprise tech wants to run the cloud operating model in its own data centers, and its take on a cloud server for the masses is now generally available.

The Cloud Computer is a server for on-premises computing in which the hardware and management software were designed to work in tandem. That's how cloud hyperscalers like AWS, Microsoft, and Google have deployed their computing resources for more than a decade, allowing them to provide computing services more efficiently than traditional servers in part because they can allow multiple customers to utilize the same server at the same time, a concept known as multitenancy.

"The case today in on-premises infrastructure is that because there is not built-in software for multitenant management, you have very, very low utilization rates of infrastructure," said Steve Tuck, co-founder and CEO of Oxide, in an interview earlier this week.

Despite the billions of dollars spent on cloud computing each year, there are still lots of companies that need to manage their own data centers for security or latency reasons and struggle to match the flexibility of cloud resources that can scale up and down with demand. Oxide thinks it can provide a server for those customers that can unlock the benefits of the cloud approach using technology that right now, retail servers sold by Dell, HPE, and Lenovo can't match.

"Those folks right now have been denied the modernity of cloud computing," said Bryan Cantrill, co-founder and CTO. "In order to be able to solve that problem, you need to be able to actually integrate and co-design hardware and software together."

Oxide launched in December 2019, and spent the last several years perfecting its design for what the company believes could be the iPhone of server hardware.

The Cloud Computer is a cabinet the size of a large industrial refrigerator that can hold up to 32 individual servers Oxide calls "sleds," which can be added or removed on the fly to increase or decrease computing capacity. The servers use one AMD EPYC 7713p processor per sled, can accommodate up to 32TBs of memory, and use custom-designed networking hardware that is integrated into the back of the cabinet.

A strong argument for cloud computing has been that adding server capacity in a traditional data center to meet increased demand can take months, between getting approval for the expenditure, getting the hardware delivered, and configuring it, Tuck said. Spinning up a new virtual machine on a cloud provider's server, however, can take minutes.

Basic Cloud Computer models are sold with 16 sleds included, and Oxide plans to deliver new sleds overnight if customers need increased capacity. The company promises those sleds can be simply inserted into the rack thanks to unique networking hardware that eliminates cabling, and while it will take a little longer to deliver a whole new rack of sleds given the size, setting it up will take less than a day, Tuck said.

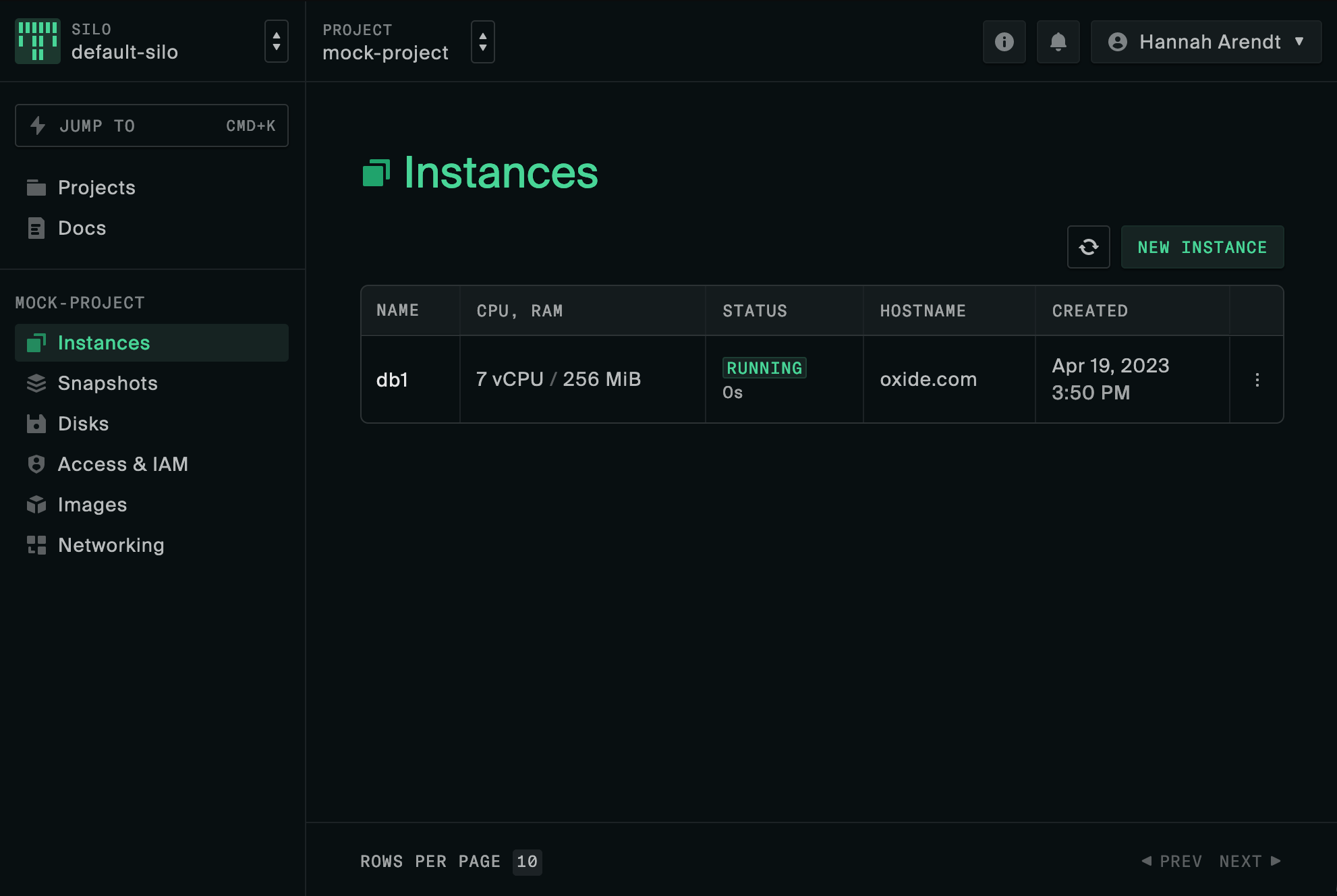

On the software side, customers can interact with the server through a web console to provision infrastructure just like they were setting up a new virtualized instance on a Big Three cloud provider, and it provides multitenancy through a custom-designed hypervisor. All the software behind the scenes is open source, but there's an ongoing subscription fee for software updates and bug fixes.

Perhaps the most tricky but essential cloud infrastructure design point that Oxide borrowed from the hyperscalers comes at the firmware level, the low-level software that controls the various components that allow servers to boot up and launch an operating system.

That firmware is generally standard across most off-the-rack servers but all the hyperscalers write their own custom firmware for their cloud servers, in part to increase operating speed but also because a bug or security vulnerability at that level can be devastating. Oxide wrote its own firmware and designed its own low-level hardware controllers to handle those tasks, rather than using commercially available products.

"The thing boots like a rocket," Cantrill said. "We control the software all the way up to the base levels of the control plane, the web console and so on, so we're able to deliver that iPhone-like experience."

Oxide also announced Thursday that it has raised $44 million in new funding led by previous investor Eclipse but joined by Intel Capital, an interesting decision by Intel's venture arm to get behind a product using AMD processors. That brings the total amount of funding raised by the company to $78 million, and it now has 62 employees, up from 15 when Protocol first covered the company in March 2020.

Oxide plans to use the new funding to expand the capabilities of the Cloud Computer, such as adding GPUs to the sleds for AI processing.

"We're obviously really interested in what's happening with GPGPUs (general-purpose GPUs), but we really needed to solve this mainstream compute problem first," Cantrill said.

Tuck and Cantrill were coy about the price of the Cloud Computer, refusing to put a number down but noting that there are a lot of configuration variables that can affect the price.

"A computer with 32 sleds costs less than an equivalent rack that has your OEM servers, and two switches, all of the enterprise virtualization software required to run it and the management software required to run it, as best we can tell from customers in the marketplace," Tuck said. After objecting to Runtime's (admittedly) back-of-the-envelope math on a comparable purchase from HPE, Tuck later provided evidence that a similar amount of computing capacity included in Oxide's product would cost around $2.3 million from Dell, not including virtualization software.

There's been a fair amount of debate over the last couple of years about "cloud repatriation," the idea that companies with an established sense of how their workloads run might be better off rolling their own data centers the old-fashioned way rather than paying cloud providers. Oxide's Cloud Computer could be an interesting signal as to how many people actually want to do that.

"We believe cloud computing is the future of computing," Tuck said. "And to be able to support that model, it cannot be gate-kept in a rental-only medium; companies and businesses need to have access to cloud computing everywhere their business runs."

This story was updated to remove a reference to equivalent pricing for a similar server at HPE that was misleading and incomplete and add a comparison from Dell that was more relevant to the Oxide product.